John Harrison, Inventor of the Marine Chronometer

John Harrison was born on March 24, 1693, in Foulby, near Wakefield, in the county of West Yorkshire, England. An 18th-century British carpenter and clockmaker, he was the inventor of the marine chronometer, a highly precise timekeeping instrument used in navigation to determine longitude at sea.

For centuries, sailors had been able to determine their latitude using celestial navigation, but accurately determining longitude at sea remained a major challenge. The solution developed by John Harrison profoundly revolutionized navigation and greatly improved the safety of long-distance maritime voyages.

The son of a carpenter, John Harrison grew up in a modest family with four siblings. From an early age, he showed a keen interest in mechanisms. Legend has it that when he contracted smallpox at the age of six, he was given a watch to distract him, and that he spent hours trying to understand how it worked.

After his family settled in Barrow upon Humber, in Lincolnshire, Harrison became a cabinetmaker and built clocks entirely out of wood. The first, completed in 1713, is now preserved in the Worshipful Company of Clockmakers’ Collection at the Guildhall. Two others, dating from 1715 and 1717, are respectively housed at the Science Museum and at Nostell Priory in Yorkshire.

In the early 1720s, Harrison received a commission to build a new clock for the town of Brocklesby Park, in North Lincolnshire.

Between 1725 and 1728, together with his brother James, also a cabinetmaker, he built at least three longcase pendulum clocks made of oak and lignum vitae, considered the most accurate of their time. These exceptional pieces are now held in museum and private collections.

In 1714, the British Parliament established the Board of Longitude, promising a reward of up to £20,000 to anyone who could devise a reliable method for calculating longitude at sea. The challenge was considerable: the acceptable margin of error was only 30 nautical miles after six weeks of navigation.

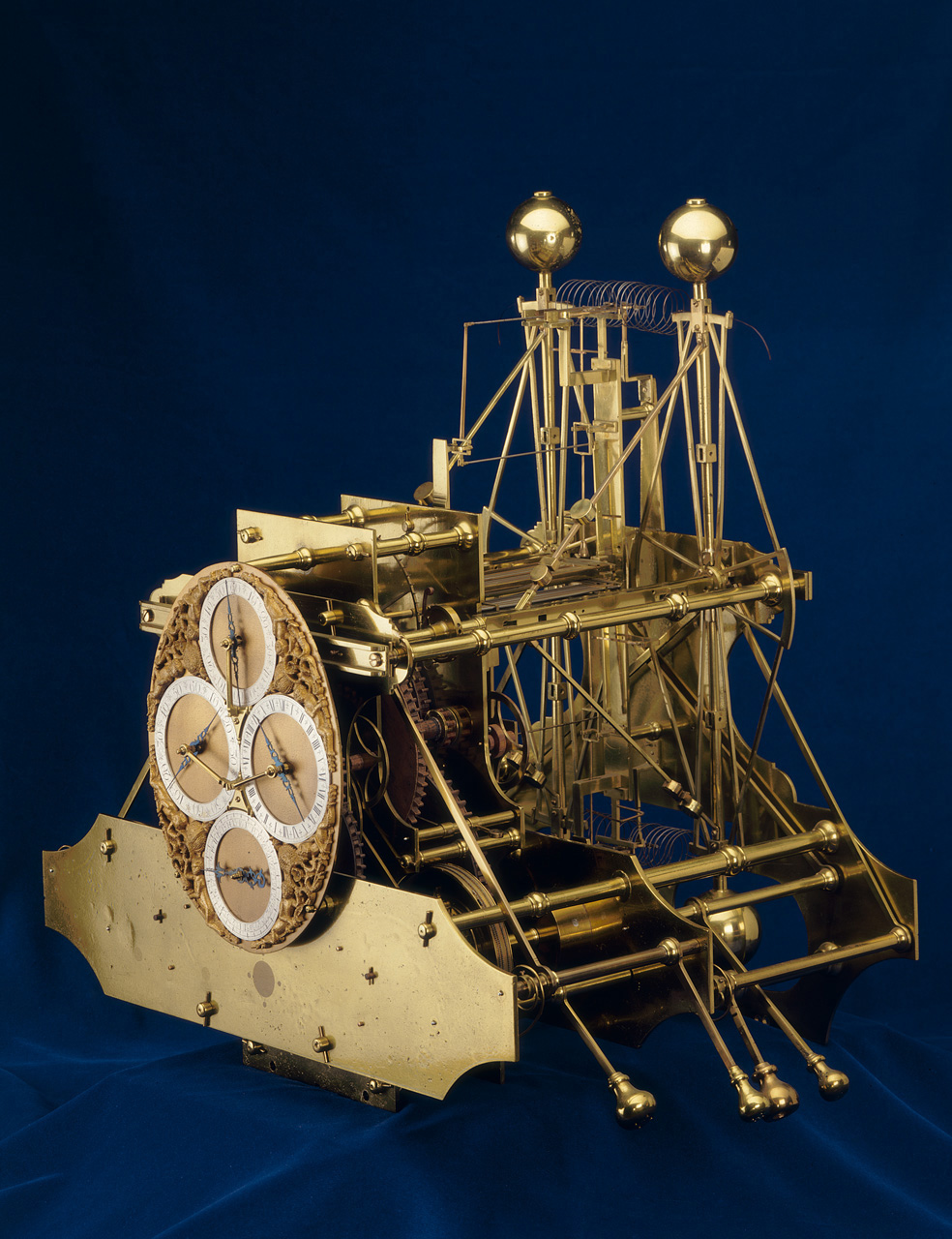

As early as 1730, Harrison took on this monumental challenge. He designed the plans for his first marine chronometer and traveled to London, where he gained the support of astronomer Edmond Halley and clockmaker George Graham. After five years of work, he completed his first model, later known as H1.

In 1736, Harrison traveled to Lisbon aboard HMS Centurion and returned on HMS Orford. Manual calculations made by the first mate indicated a position 60 miles too far east, whereas the position calculated by Harrison using his H1 was accurate. Although this was not the transatlantic voyage required by the Board of Longitude, it impressed the jury enough for Harrison to be awarded a grant of £500.

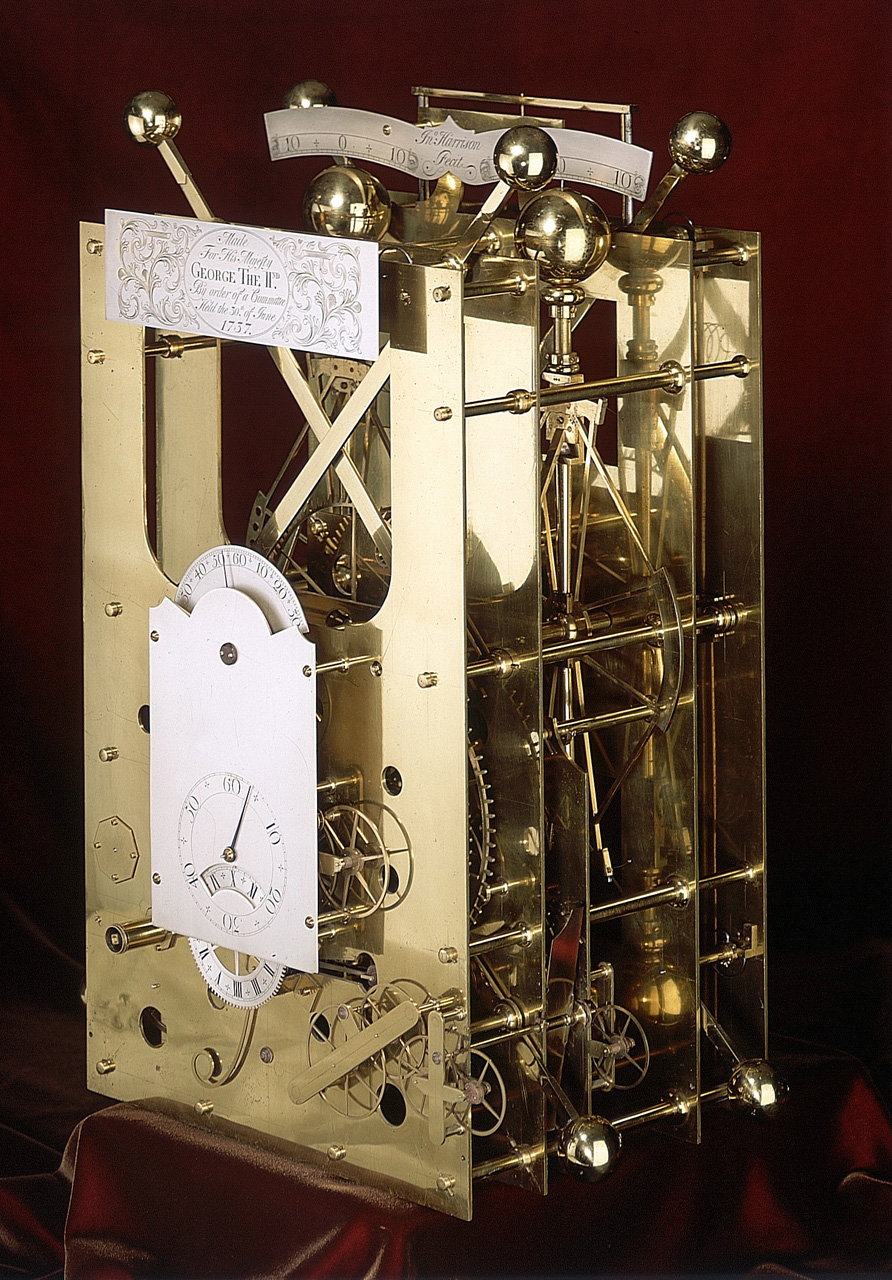

Harrison then began building his second chronometer, H2, which was more compact. In 1741, after three years of construction and two years of testing on land, H2 was ready. However, the War of the Austrian Succession between England and Spain prevented testing it on a transatlantic voyage. While awaiting the end of the war, the Board of Longitude granted him another £500 to assist him.

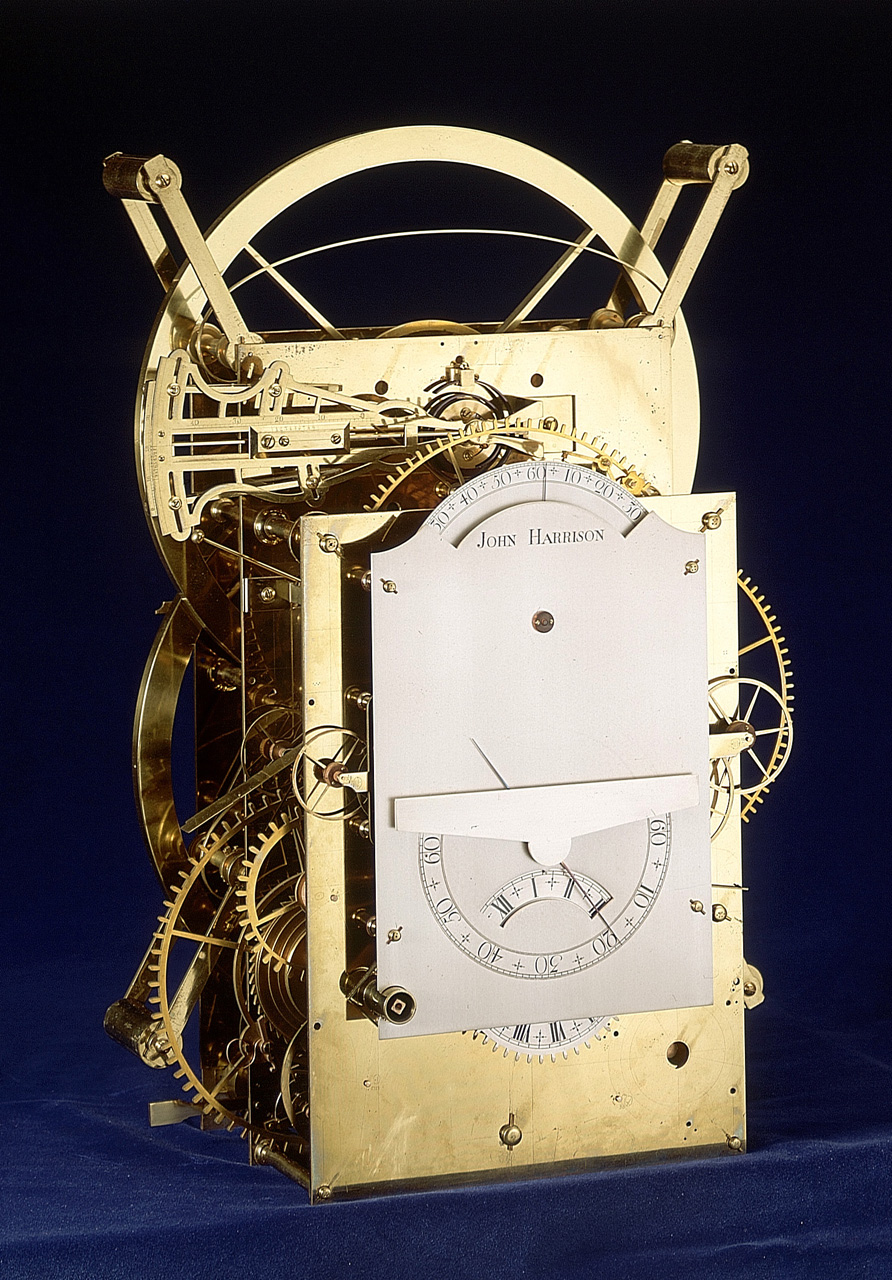

As Harrison discovered a design flaw in the balance systems, he began working on his third chronometer, H3, but without achieving results that fully satisfied him.

It was with H4, completed in 1759, that Harrison achieved his decisive breakthrough. Unlike the previous models, H4 resembled a large pocket watch and featured an innovative escapement and exceptional accuracy.

Harrison, now 68 years old, sent his son William on the required transatlantic voyage. In 1761, William boarded HMS Deptford, bound for Jamaica. Upon arrival, calculations showed that the H4 chronometer was slow by 5 seconds, corresponding to a longitude error of 1.25 minutes, or about one nautical mile. Harrison believed this result would earn him the prize, but the jury refused, claiming that luck had played a role. The matter was brought before the British Parliament, which agreed to grant only a compensation of £5,000, an offer Harrison rejected.

A new voyage was organized to provide further proof. HMS Tartar sailed to the island of Barbados. The H4 chronometer showed a time discrepancy of 39 seconds, resulting in a positional error of about fifteen kilometers. Reverend Nevil Maskelyne, who also made the voyage, calculated longitude using the position of the Moon and arrived at an error of 48 km. The results were presented to the Board of Longitude in 1765, which again concluded that chance had played a significant role. Parliament offered half of the prize, promising the remaining half once similarly accurate results could be achieved using copies of the H4 chronometer. Maskelyne, having become Astronomer Royal and a member of the Board of Longitude, persuaded the other jurors not to commission copies of the H4.

While the H4 remained in the hands of the jury for examination, Harrison began working on a new chronometer, H5.

After three years of waiting, Harrison grew impatient and appealed directly to King George III. He entrusted the H5 to the king for ten weeks, from May to July 1772, during which daily measurements showed that the H5 erred by about one-third of a second per day.

The king was impressed and urged Parliament to award the prize. In 1773, Parliament granted a payment of £8,750 (only part of the total prize, but already a considerable sum) to the elderly Harrison, now 80 years old.

John Harrison died on March 24, 1776, at Red Lion Square in the Bloomsbury district of London, on his 83rd birthday. He was buried in the churchyard of St. John’s Church in Hampstead, where his second wife, Elizabeth, and their son William are also interred.

From 1730 until the end of his life, Harrison devoted himself exclusively to the creation of marine chronometers for determining longitude. Today, the chronometers H1, H2, H3, and H4 are preserved and displayed at the Royal Observatory in Greenwich, London, bearing witness to the ingenuity of a man who forever changed the history of maritime navigation.

References:

https://fr.wikipedia.org/wiki/John_Harrison_(horloger)

https://www.longitude-heritage.com/longitude