Towards greater representation of women in the African maritime industry

In Africa, the percentage of women working in the maritime industry remains significantly lower than on other continents. Although overall statistics for the whole of Africa are lacking, some national data reveal the low presence of women in this crucial sector.

In 2017, the Togolese port platform had just 67 women out of 783 employees, representing around 9% of the workforce.

Similarly, in Benin, only 82 of the 512 employees of the Autonomous Port of Cotonou in 2021 were women, or 16%.

In Nigeria, in 2019, women made up 9.3% of seafarers.

In Ghana, women accounted for 16% of staff at the Ghana Ports and Harbours Authority in 2021.

In South Africa, an ISS article notes that “only 15 out of 70 marine pilots are women”, or 21%.

However, despite their small numbers, women are very present in the port industry, particularly at administrative level, where they play an essential role in the growth of the organisation. They occupy various positions at different levels of the chain, whether executive, managerial or operational, ranging from crane operator to General Manager of the port.

For example, of the 67 women employed in 2017 by the Togolese port hub, 49 (75%) held positions of responsibility in Human Resources, the Port Community (Alliance pour la Promotion du Port de Lomé), the Medical and Social Centre and General Administration.

In Nigeria, Hadiza Bala Usman made history by becoming the first female Director General of the Nigerian Ports Authority (NPA).

Moreover, women have always played a role in this traditionally male-dominated sector. They were present in ports, private shipping companies and state institutions such as African shippers’ councils, African shipping companies, national maritime agencies and ministries responsible for the maritime economy or transport.

Moreover, women have always played a role in this traditionally male-dominated sector. They were present in ports, private shipping companies and state institutions such as African shippers’ councils, African shipping companies, national maritime agencies and ministries responsible for the maritime economy or transport.

Today, they can also be found in navigation-related jobs, occupying positions such as bridge watch officer, engine watch officer, ship’s captain, and many others.

Research shows that companies with women at the top perform better. There is a lot of evidence to support the fact that investing in women is one of the most effective ways of raising communities, companies and even states.

Challenges and Obstacles Facing Women in the Maritime Sector in Africa

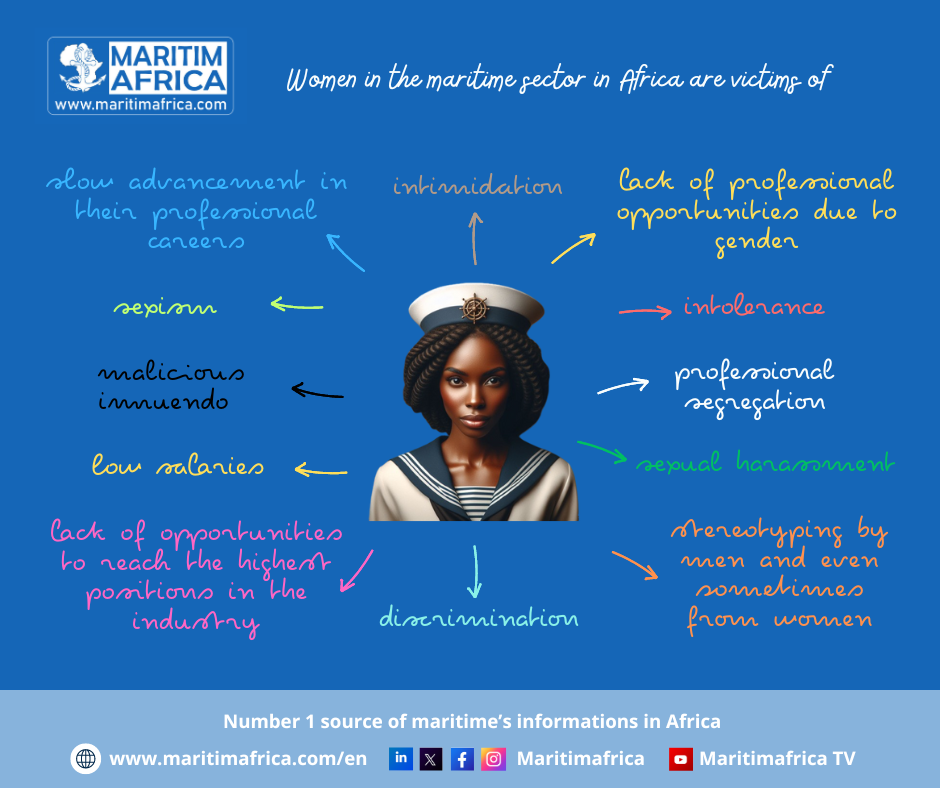

Yet they continue to face many challenges, including discrimination, sexism, intolerance, intimidation, malicious innuendo, lack of professional opportunities due to gender, slow advancement in their professional careers, low salaries, stereotyping by men and even sometimes from women, lack of opportunities to reach the highest positions in the industry, professional segregation, not to mention sexual harassment.

Women also have to make extra efforts, or even work twice as hard, to progress in this sector. They are seen by their male counterparts as the weak links in the company. Their intelligence and skills are questioned by their male colleagues. When they have to manage men, they have to demonstrate a high level of leadership, patience and diplomacy to gain acceptance and the trust of their subordinates.

An international study revealed that although 1.28% of seafarers are women, 60% of them reported having been victims of gender-based discrimination on board ships.

Female seafarers who are victims of sexual harassment are often reluctant to lodge a complaint, for fear of social and personal consequences such as continued harassment or isolation, or even the loss of their job.

In Africa, there have been very few incidents of this kind that have received media coverage, even though some women working in the African maritime industry are nevertheless victims.

The case of Akhona Geveza, a cadet of the South African National Port Authority (Transnet), who was doing her training on board the container ship Safmarine Kariba, was reported missing at around midday on 24 June 2010. After hours of searching, her body was found at sea by local police near the port of Rijeka, Croatia.

A Croatian police report on the incident concluded that she committed suicide after taking pills and also drinking poisoned liquids. South African newspapers had reported that she had earlier told a colleague, Cadet Nokulunga Cele, that she had been raped by the Ukrainian chief officer of the ship.

“According to Safmarine, as soon as they learned of the allegations against Ms. Geveza, they ordered the chief officer on board the ship to be relieved of his duties,” reveals gCaptain.

Akhona Geveza’s case is unfortunately not an isolated incident. Similar cases of harassment, aggression and discrimination persist in this vital sector.

Legislation and Conventions to Protect Women in the Maritime Sector in Africa

In Africa, there is no legislation or enforcement mechanisms to protect women in the maritime sector. The « 2050 Africa’s Integrated Maritime Strategy (2050 AIM Strategy) », simply recognizes the importance of gender equality and the need to address imbalances within the sector.

At international level, however, we note :

- the Maritime Labour Convention 2006 (ILO 2006); and

- the Resolution on Harassment and Bullying, including Sexual Assault and Sexual Harassment, in the Maritime Sector, adopted by the Special Tripartite Committee (STC), under Article XIII of the Maritime Labour Convention, 2006, as amended (MLC, 2006).

The International Labour Organisation (ILO) is also working to consolidate its many maritime labour Conventions into a single, universally accepted text to improve the working conditions of all seafarers, both men and women.

In addition to the above-mentioned conventions, African legislators are also relying on those relating to labour and gender equality, namely

- ILO Convention 190 (C190 for short), which is the first international treaty to recognize the right of everyone to a world of work free from violence and harassment, including gender-based violence and harassment;

- the Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination against Women, 1979;

- the Equal Remuneration Convention (No. 100) concerning Equal Remuneration for Men and Women Workers for Work of Equal Value, 1951;

- Convention No. 111 concerning Discrimination in Respect of. Employment and Occupation, 1958.

On a continental level, we can cite :

- the African Charter on Human and Peoples’ Rights, 1981, also known as the “Banjul Charter”;

- the Protocol to the African Charter on Human and Peoples’ Rights on the Rights of Women in Africa, 2003, also known as the Maputo Protocol;

- the Local and Regional Governments’ Charter for Gender Equality in Africa, 2022;

- etc.

At national level, these are labour codes, national constitutions, etc.

For example, in Morocco, Article 9 of the Labor Code prohibits any discrimination against employees on the basis of gender.

In Senegal, Article 25 of Law No. 2001-03 of January 22, 2001 on the Constitution, as amended, prohibits any discrimination between men and women in employment, wages and taxes. Also, Article L.105 of the Senegalese Labor Code stipulates that « Under equal conditions of work, professional qualification and performance, wages are equal for all workers, regardless of their origin, sex, age and status. »

Recommendations to Support Women in the Maritime Sector in Africa

To combat the challenges faced by women in the maritime sector, a number of initiatives can be put in place by governments, institutions, associations and all other stakeholders:

- Organise awareness-raising campaigns on equal opportunities and anti-discrimination in the maritime sector.

- Implement and enforce zero-tolerance policies on discrimination, harassment and sexism in maritime workplaces, with clear sanctions for offenders.

- Adopt laws and regulations that guarantee equal opportunities for women in recruitment, promotion and access to management positions in the maritime sector.

- Implement gender quotas or diversity targets to ensure equitable representation of women at all levels of the maritime industry in Africa.

- Implement initiatives to increase the representation of women in management and decision-making positions within maritime companies and organisations.

- Create professional support networks exclusively for African women in the maritime sector, providing opportunities for networking, mentoring and sharing experiences.

- Organise events and conferences focusing on female leadership and the achievements of women in the African maritime sector to inspire them and promote their career advancement.

- Establish confidential and accessible reporting mechanisms for discrimination, harassment and bullying in the workplace.

- Provide psychological and legal support to victims, including counselling services and protection resources.

In conclusion, although persistent challenges hinder the full integration of women into the African maritime industry, significant progress is being made with the rise of talented women to leadership positions and the growing recognition of their vital contribution to this vital sector. To ensure equitable representation and eliminate persistent barriers such as discrimination and harassment, it is imperative that governments, business and civil society step up their efforts. By adopting inclusive policies, strengthening legislation and promoting a culture of respect and equality, Africa can truly pave the way for a more diverse, dynamic and prosperous maritime industry for all.

By Pascaline ODOUBOUROU,

By Pascaline ODOUBOUROU,

Specialist in Port and Maritime Management,

Specialist in the Blue Economy, Gender in the Blue Economy,

Founder and Editor-in-Chief of MARITIMAFRICA,

Co-Founder of Blue Women Africa